A N N H O L Y O K E . O R G | A M E T H O D O L O G I C A L C A T A L O G U E O F W O R K S

48 | F O U N D

Eight wall sculptures, 2010 [executed 2012]

Painted pressboard, 15/32" to 7/8" [ 12mm to 22mm ] thick

Diameters of 60", 53.5", 47.5", 45", 40", 38", 36", 32.5", 31" [ 152.4 cm, 143.5 cm, 120.7 cm, 114.3 cm, 101.6 cm, 91.4 cm, 82.6 cm, 78.7 cm ].

Hanging ( altar- ) piece, 2010 [executed 2012]

Painted wood

79 x 79 x 7 inches [ 201 x 201 x 18 cm ].

This is a piece I found —or at least one that showed up on my computer screen—as I was working on the catalogue entry above dealing with my half-hour filmwork

TIDE; or, the Bore and had just discovered that two smaller bells were added to the tower at St. Ethelbert’s,

Littledean, in 2005, so that instead of the six

that Blum and I had recorded in 1996, eight bells now rang out there.

As the 40,320 changes on eight bells take not thirty

minutes but over twenty-two hours to ring, had the peal been increased but a few years earlier, I would never have contacted Littlrdean’s bell-secretary, Mary Pollard, nor seen the

Severn Bore in the light of a full moon, .

The two new bells had been cast at London’s Whitechapel Bell Foundry, on whose website I learned a good deal about the business side of bells. The firm had

been founded in 1570, during the reign of Elizabeth I. In 1858, the Palace of Westminster’s thirteen-and-a-half-ton Big

Ben was cast there, as had been Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell, in 1752—coincidentally, the same year that five of the

first six bells at Littledean had been founded by William Evans in Chepstow—the sixth having being cast in 1894 by Gillett & Johnston, Croydon, who were, in turn, the founders of the ten-ton copy of the Liberty Bell that has hung in Berlin’s Rathaus Schöneberg since 1950 .

Hanging the Freiheitsglocke (“Liberty Bell”), Berlin-Schöneberg, October 1950. [Photo: unknown]

Whitechapel’s on-line catalogue of “Prices of Standard [ Tower ] Bells” listed thirty-seven bells, whose nominal pitches comprised three complete, consecutive

chromatic scales, from C to C, providing what I was convinced were raw data for a new piece. The list gave each individual bell’s note-name, its diameters at lip and crown, its height, its

weight, and its price (in pounds sterling), all arranged in six columns and trussed up in a delightfully no-nonsense grid. However, it was the bells’ diameters that most spoke to me. I imagined

the bronze darkness of their mouths, light streaming about their outer edges and pouring through the openings I envisioned where the disks of their crowns should be, so that the bells appeared as

wide rings, or flat tori. It soon became clear that my new work would consist of eight such objects—whose diameters, inside and out, were to be determined by those of the lowest octave in the

list—and be titled FOUND.

The works documented above ought to make it abundantly clear that concentricity and its relationship to concentration are among my prime concerns. In Geoffrey

Chaucer’s Hous of Fame the very transport of sound in air is described as functioning concentrically—as being like

the progress of wavelets in water: Every sercle causynge other / Wydder than hymselve was—and every contemporary computer user and comic or cartoon reader is familiar with the use of

successive, or progressive, concentric arcs to denote the ringing and reverberations of everything from mobile phones and loudspeakers to, well, bells.

The how, and why of constructing an actual work out of this material began to fall into place as I was confronted with the plan to develop a Raumwerk for

Berlin’s St. Matthäus-Kirche (St. Matthew’s Church). This is a church with an ambitious agenda of visual and musical art events and undertakings, located—and sticking out like a sore thumb—as the

only extant pre-war structure in Berlin’s Kulturforum, the dim cultural candle West Berlin held to the glory of the East’s Museumsinsel (“Museum Island”), which itself had been

a bequest of the East-German regime’s imperial and bourgeois antecedents.

The façade of Andreas Stüler’s Mattäus-Kirche with banners for FOUND and ”Matthäus-Musik,” a concert series with the Berlin Philharmonic's Scharoun Ensemble; a section of the flat roof of Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie is visible to the left.

Designed and built by Andreas Stüler—whose teacher had been none other than Friedrich Schinkel, the region’s patron saint of architecture—St. Matthew’s was consecrated in 1846. It seems to have soon become home to one of the largest, and most affluent, parishes in all Berlin, which by 1920 was itself the third largest city in the world. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, unforgotten Lutheran theologian, pastor, and founding member of the Bekennende Kirche (“Confessing Church”), was ordained at St. Matthew’s, in 1931. Martyred for his pains—which included participation in a plot against the Führer—Bonhoeffer was murdered at the Flossenbürg concentration camp, just three weeks before the Third Reich’s capitulation.

Bronze plaque by Johannes Grützke, beside the entrance to the Matthäus-Kirche,

commemorating Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945). Photo © Andreas Steinhoff.

The private and privileged residences in the Matthäikirchplatz’s immediate vicinity had, however, stood in the way of the National-Socialists’ plans for Germania, the hyperbolic polis from whose marble halls they planned to rule the world. As a result, most of the area’s buildings had been razed even before the war came along to finish off what Fascist hubris had begun. These days, the properties neighboring the church primarily house cultural institutions in structures built between 1960 and 1998, including the Neue Nationalgalerie (which opened its doors in September 1968 as the only building Mies van der Rohe realized in Germany after World War II), the Gemäldegalerie and Kupferstichkabinett, the Kunstgewerbemuseum, the Staatsbibliothek, as well as the Philharmonie with its Kammermusiksaal.

Beyond the Kulturforum, visible from the church’s steps and belfry, rise the bumptious forms of the hastily projected and erected corporate towers of Potsdamer Platz, in which I can’t help but see the spires of Oz’s Emerald City, convinced we’ll wake one of these days to find them gone, and ourselves right back in Cold War Kansas. These spectral towers of undead, post-separation Potsdamer Platz—once a bustling square, the Continent’s most frequented traffic center, in fact, and the site (as legend has it), in 1924, of Germany’s first traffic lights—were thrown up on what had, for half a century after the war, been a death strip in the shadow of the Wall, the well-guarded habitat of countless generations of wild rabbits and rare plants.

This is, in a word, haunted and hallowed ground.

Looking north from the bell tower of St. Matthew’s, whose shadow falls on the Philharmonic Chamber Music Hall (with the Reichstag visible, immediately to its left, above the trees of the Tiergarten); foreground (left): Museums of the Kulturforum. Background (left): Federal Chancellery and parliamentary buildings; background (right): Potsdamer Platz.

The church itself was in ruins, when the city came to after the battle for Berlin, and did not reopen for business until 1960. With its perfectly rebuilt façade and severely straitened, unambiguous interior—very much in the post-war era’s no-frills Modernist style, virtually devoid of ornamentation (and congregation)—St. Matthew’s is presently the smallest parish in the city, with the great majority of its visitors coming strictly for the art and music presented there.

Such cultural events are often worked into liturgical contexts : weekly concert–services present predominantly New Music that, parallel to a program of what you’d

have to call art exhibitions—though I find the terminology, and even the concept, out of keeping with a site that has never been deconsecrated—form the backdrop for an established series of

installations entitled Das andere Altarbild ( “The other altarpiece” ), which displays just that: artworks as retables, hanging or standing in the apse, above and behind the polished

stone Communion table. In fact, what initially led me to St. Matthew’s was the notion that the DONNE TRIPTYCH should be a part

of this series, either as a solitary piece—closed during the Lenten period of fasting, abstinence, and penitence, and then opened to the joy of Easter Sunday—or, at a different season of the

Christian year, complemented in the aisles by a carefully selected sampling from my earlier ecclesiastically flavored works—PSALTER

I, II, and III, for instance, or TIMEO flanked by EARTH AIR FIRE WATER AETHER.

This seemed a perfectly good plan until I had to admit two things to myself : first, that setting up a wall-piece weighing nearly two hundred pounds as a

free-standing object would involve building a heavy scaffold to support it, and thus make a complete perceptual muddle of what was altar, what was piece, and what support; and second, that,

while the other objects I proposed to show were definitely apropos—and might have been shown to advantage, hanging on the

spare, white walls along the aisles to either side, between the five pairs of window recesses, with their rounded arches—they might well make of the church a better sort of marché aux

puces.

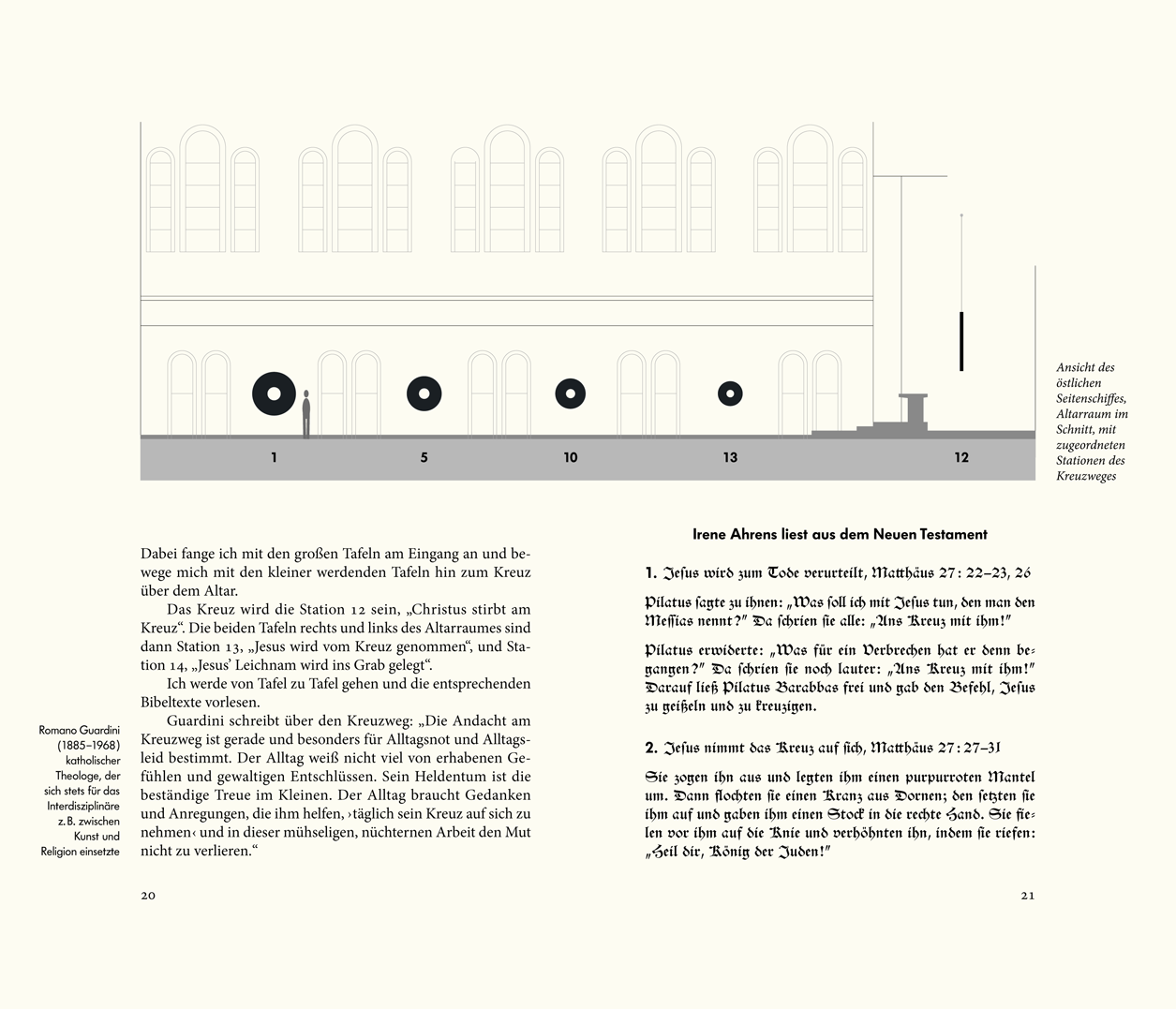

FOUND: perspective view of the eastern aisle of the Matthäus-Kirche.

FOUND’s eight hollow tori, on the other hand, installed upon those same eight walls, might act much as the figure zero does—itself not an integer, it serves to order Number—organizing the church’s spaces and marking their rhythms. These unprepossessing ring-shaped “found objects” would constantly conduct the viewer’s gaze back to the church’s interior—its bareness, flooded with daylight—and to the apse and its altar.

The eight “CD-shaped” pressboard tondi lining the aisles were evenly coated with a dark, bronze-colored paint, whose finish has a sheen level under ten percent— just enough, that is, to catch the light

and resemble dull metallic surfaces . Originally, I had intended these wheel-like forms to increase in diameter as they “rolled” toward the apse, so that a visitor entering the church

would experience them first, in

perspective, as more or less the same size, and, if only unconsciously, feel himself grow smaller as he approached the altar. Hence, my initial plans were drawn up to produce this effect.

Apse (cross section) with west aisle (elevation) as originally conceived, above;

east aisle (elevation) with apse (cross section) as originally conceived, below.

In the event, however, I chose to reverse the order of the disks, so that their perspective first seemed to extend the distance visitors had to traverse on their way to the altar, conversely making the “return trip" appear all the shorter.

Apse (cross section) and west aisle (elevation) as executed, above;

east aisle (elevation) and apse (cross section) as executed, below.

The piece I designed to hang above and behind that altar was as undemanding in construction as the eight the pancaked “matryoshki,” in the aisles —those stations of a planar mater dolorosa—namely, an X-shaped “Saint Andrew’s” cross, fashioned from two eighteen-by-ten-centimeter ( seven-by-four-inch ) building timbers, each 2.7 meters long, and painted a deep and “dead flat” black. The featureless round panels, with their empty, gawping centers, thus came to stand for repeatedly asked questions to which the cross provides an answer, as an X marking the spot, and as an ideogram for Christ : Χ, chi, for ΧρίστόϚ. The empty disks play as well on the image of the open eye as the gateway of perception leading to a mental synthesis of what is seen. Like so many focal points, four pairs of white, Brobdingnagian pupils—enclosed within dark irises, and separated by the cranial cavity of the nave between them—collect the viewer’s gaze and throw it back where it belongs : into the church, where it meets with a resonance at once architectonic and ideal, wandering until it finds the black cross hanging from the half dome of the apse’s recess.

FOUND: Apse with altarpiece (elevation), Matthäus-Kirche, Berlin.

The open form of this cross—the crux decussata, whose origins are to be found in the crossed brands of the altar-fire—is both a sign of warning and a reminiscence of the Vitruvian man, who boldly measures his proportions against the matchless perfection of square and circle—while never quite freeing himself from the connotations of a victim splayed upon the saltire’s arms and legs. More so than that of the customary Latin cross—or crux immissa, to whose obscenity we’ve by now become all but immune—the form of the Saint Andrew’s Cross can still make its potential as an instrument of death-dealing torture felt and, thus, crucifixion real for us.

FOUND was presented in the Matthäus-Kirche, in 2012, during the forty days of Lent, the

Christian Church’s period of self-denial and introspection beginning on Ash Wednesday and presaging the annual commemoration of Good Friday’s Passion and Easter Sunday’s Resurrection. At

the “artist’s talk” held on 1 March, the massed and measured strains of works for organ, Peniel ( 1968 ) and Found Music ( 2011 ), by John Patrick Thomas were heard grappling in the

church’s—and the Raumwerk’s—midst. Found Music was again performed at the Good Friday evening service.

John Patrick Thomas, Found Music, for organ, 2011.

Yet even without the Crucifixion and the Church, without Christian iconography, without considering, that is, FOUND’s site-specific eloquence, I find the work surrenders little of its meaning . It is no less viable on its own, no less valid in its own right. Indeed, the piece may only fully assumes its final, profane consequence without such consecrated walls. As the mute, disembodied mouths of bells pose and re-pose questions of our core, our quintessence, our crux, the cross’s black form swallows all light that dares to fall upon it. Self-absorbed, self-centered, and self-seeking—suspended vulnerable and forthright in the void—a hitherto unknown, unnamed quantity gives its brazen answer tongue : I am here ! This is my mark !

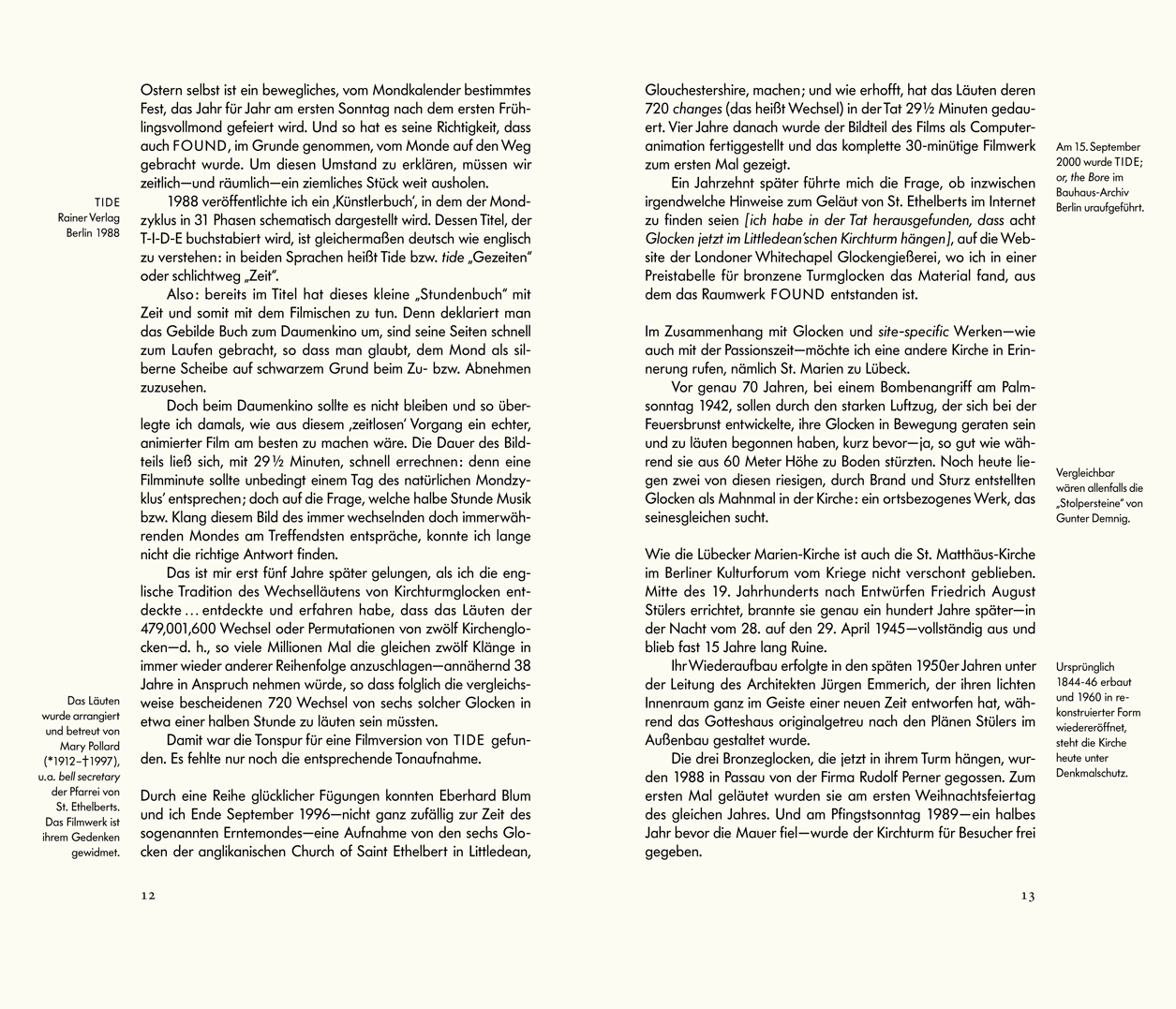

FOUND: cover and spreads of the publication documenting the "artist’s talk” held on 1 March 2012, at the Matthäus-Kirche.